The government, which has been in power for a decade and a half, has a peculiar relationship with higher education rankings. At the beginning of the period, the prime minister announced a program to get Hungarian universities into the top 200, which we immediately wrote about, saying that it was both impossible and unnecessary.

In the mid-2000s, we saw signs of sobering up when the then minister responsible for higher education saw the best chances of reaching the top 200 in the subject-specific lists, which was realistic on the one hand and, with certain restrictions, could even be a meaningful goal on the other. However, in the last two to three years, the goal has become to reach the “top 100.” Unfortunately, in light of this year’s global rankings, this ambition does not seem realistic.

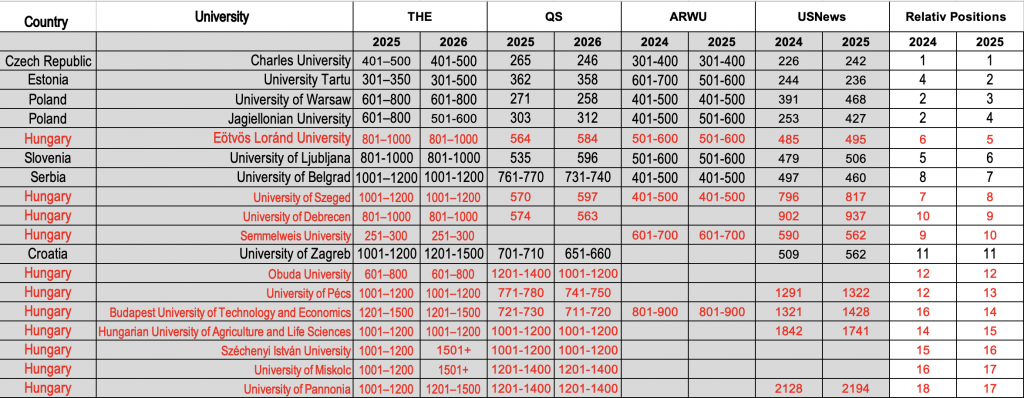

The ranking positions of the 11 Hungarian universities that made it into one of the four more seriously taken global rankings have hardly changed overall compared to last year, with six of the eleven moving up and sixteen remaining unchanged. There were two significant advances in previous years: in 2023, Óbuda University jumped from the 1001-1200 group to the 601-800 group for 2024, but this trend did not continue this year. The Semmelweis march, which was accompanied by high government hopes (and is indeed commendable) on THE’s list, also seems to have stalled. Two years ago, Hungarian universities achieved their best ranking ever, placing between 200 and 250, but last year, contrary to government expectations, they did not move up but down one place to 250-300, where they remained this year. (During this period, THE changed its methodology for calculating publication performance due to publication anomalies that put SE and Óbuda University in a more favorable position. It still holds a leading position in the post-socialist region, as only three other Austrian medical universities rank higher than it, apart from the University of Vienna (only medical universities are included in the subject-specific list). In the least hackable ranking, the ARWU (“Shanghai ranking”), we saw a significant positive change earlier, clearly due to Katalin Karikó’s Nobel Prize, but its impact this year was only enough to maintain the 401-500 group (along with improved publication performance).

Looking at the four rankings together, it is clear that the ranking of Hungarian universities has not changed at all in the former Soviet sphere of influence. ELTE continues to lead the second group, directly behind the four leading institutions (Charles University in Prague, the University of Tartu in Estonia, and the two Polish institutions, Jagiellonian University and the University of Warsaw). Szeged, Debrecen, and Semmelweis, which are ranked after Ljubljana, Belgrade, and Zagreb. The other Hungarian institutions are mostly in the second thousand group of universities measured by the rankings, with the exception of the Technical University’s 700-800 category on the QS and ARWU lists and Pécs’s better QS ranking.

Of course, this does not mean that Hungarian universities do not have departments and research laboratories that are among the best in the world. In addition, another part of them excellently adapts world science for education and R&D. And these lists reveal essentially nothing about the effectiveness and quality of education. The vast majority of Hungarian students do not face a real dilemma between choosing Anglo-Saxon, Chinese, and German-French universities, not only because of their inaccessibility, but also because of the expectations of domestic social and labor market integration. For this reason, it is neither practical nor beneficial for Hungarian higher education policy, and especially not for institutional strategies, to focus on global rankings. This is particularly true in countries with medium (higher education) development, where such a distortion can lead to organic university movements being overshadowed by local socio-economic needs, the erosion of national culture, and the inefficient use of resources.

After all, global university rankings are of very limited value in measuring performance and quality; they are best suited to measuring publication activity in line with the professional culture of the natural sciences, internationality in terms of geographically and culturally unequal conditions, and reputation. They are certainly not suitable for reflecting the real effects of higher education restructuring (“foundationization”).

A significant portion of the indicators used in these rankings come from the publishing industry, where thematic and geographical biases, networks, and routines that are detrimental to truly exciting scientific achievements are at work. It is gratifying that Hungarian universities have also joined the COARA initiative, which seeks to replace the one-sided focus on quantity and article writing with tools that capture quality in a variety of ways. If the government supports this, it would greatly help in the meaningful development of Hungarian universities.

Dr. habil György Fábri (1964) is an habilitated associate professor (Institute of research on Adult Education and Knowledge Management, Faculty of Education and Psychology of Eötvös Loránd University), head of the Social Communication Research Group. Areas of research: university philosophy, sociology of higher education and science, science communication, social communication, church sociology. His monograph was published on the transformation of Hungarian higher education during the change of regime (1992 Wien) and on university rankings (2017 Budapest). He has edited several scientific journals, and his university courses and publications cover communication theory, university philosophy, science communication, social representation, media and social philosophy, ethics, and church sociology.

Dr. habil György Fábri (1964) is an habilitated associate professor (Institute of research on Adult Education and Knowledge Management, Faculty of Education and Psychology of Eötvös Loránd University), head of the Social Communication Research Group. Areas of research: university philosophy, sociology of higher education and science, science communication, social communication, church sociology. His monograph was published on the transformation of Hungarian higher education during the change of regime (1992 Wien) and on university rankings (2017 Budapest). He has edited several scientific journals, and his university courses and publications cover communication theory, university philosophy, science communication, social representation, media and social philosophy, ethics, and church sociology.

Dr. Mircea Dumitru is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (since 2004). Rector of the University of Bucharest (since 2011). President of the European Society of Analytic Philosophy (2011 – 2014). Corresponding Fellow of the Romanian Academy (since 2014). Minister of Education and Scientific Research (July 2016 – January 2017). Visiting Professor at Beijing Normal University (2017 – 2022). President of the International Institute of Philosophy (2017 – 2020). President of Balkan Universities Association (2019 – 2020). He holds a PhD in Philosophy at Tulane University, New Orleans, USA (1998) with a topic in modal logic and philosophy of mathematics, and another PhD in Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (1998) with a topic in philosophy of language. Invited Professor at Tulsa University (USA), CUNY (USA), NYU (USA), Lyon 3, ENS Lyon, University of Helsinki, CUPL (Beijing, China), Pekin University (Beijing, China). Main area of research: philosophical logic, metaphysics, and philosophy of language. Main publications: Modality and Incompleteness (UMI, Ann Arbor, 1998); Modalitate si incompletitudine, (Paideia Publishing House, 2001, in Romanian; the book received the Mircea Florian Prize of the Romanian Academy); Logic and Philosophical Explorations (Humanitas, Bucharest, 2004, in Romanian); Words, Theories, and Things. Quine in Focus (ed.) (Pelican, 2009); Truth (ed.) (Bucharest University Publishing House, 2013); article on the Philosophy of Kit Fine, in The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, the Third Edition, Robert Audi (ed.) (Cambridge University Press, 2015), Metaphysics, Meaning, and Modality. Themes from Kit Fine (ed.) (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

Dr. Mircea Dumitru is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (since 2004). Rector of the University of Bucharest (since 2011). President of the European Society of Analytic Philosophy (2011 – 2014). Corresponding Fellow of the Romanian Academy (since 2014). Minister of Education and Scientific Research (July 2016 – January 2017). Visiting Professor at Beijing Normal University (2017 – 2022). President of the International Institute of Philosophy (2017 – 2020). President of Balkan Universities Association (2019 – 2020). He holds a PhD in Philosophy at Tulane University, New Orleans, USA (1998) with a topic in modal logic and philosophy of mathematics, and another PhD in Philosophy at the University of Bucharest (1998) with a topic in philosophy of language. Invited Professor at Tulsa University (USA), CUNY (USA), NYU (USA), Lyon 3, ENS Lyon, University of Helsinki, CUPL (Beijing, China), Pekin University (Beijing, China). Main area of research: philosophical logic, metaphysics, and philosophy of language. Main publications: Modality and Incompleteness (UMI, Ann Arbor, 1998); Modalitate si incompletitudine, (Paideia Publishing House, 2001, in Romanian; the book received the Mircea Florian Prize of the Romanian Academy); Logic and Philosophical Explorations (Humanitas, Bucharest, 2004, in Romanian); Words, Theories, and Things. Quine in Focus (ed.) (Pelican, 2009); Truth (ed.) (Bucharest University Publishing House, 2013); article on the Philosophy of Kit Fine, in The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, the Third Edition, Robert Audi (ed.) (Cambridge University Press, 2015), Metaphysics, Meaning, and Modality. Themes from Kit Fine (ed.) (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). Mr. Degli Esposti is Full Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Deputy Rector Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Dean of Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Head of Service for the health and safety of people in the workplace, President of the Alma Mater Foundation and Delegate for Rankings.

Mr. Degli Esposti is Full Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Deputy Rector Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Dean of Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, Head of Service for the health and safety of people in the workplace, President of the Alma Mater Foundation and Delegate for Rankings.

Ben joined QS in 2002 and has led institutional performance insights function of QS since its emergence following the early success of the QS World University Rankings®. His team is, today, responsible for the operational management of all major QS research projects including the QS World University Rankings® and variants by region and subject. Comprising over 60 people in five international locations, the team also operate a widely adopted university rating system – QS Stars – and a range of commissioned business intelligence and strategic advisory services.Ben has travelled to over 50 countries and spoken on his research in almost 40. He has personally visited over 50 of the world’s top 100 universities amongst countless others and is a regular and sought after speaker on the conference circuit.Ben is married and has two sons; if he had any free time it would be spent reading, watching movies and skiing.

Ben joined QS in 2002 and has led institutional performance insights function of QS since its emergence following the early success of the QS World University Rankings®. His team is, today, responsible for the operational management of all major QS research projects including the QS World University Rankings® and variants by region and subject. Comprising over 60 people in five international locations, the team also operate a widely adopted university rating system – QS Stars – and a range of commissioned business intelligence and strategic advisory services.Ben has travelled to over 50 countries and spoken on his research in almost 40. He has personally visited over 50 of the world’s top 100 universities amongst countless others and is a regular and sought after speaker on the conference circuit.Ben is married and has two sons; if he had any free time it would be spent reading, watching movies and skiing.

Anna Urbanovics is a PhD student at Doctoral School of Public Administration Sciences of the University of Public Service, and studies Sociology Master of Arts at the Corvinus University of Budapest. She is graduated in International Security Studies Master of Arts at the University of Public Service. She does research in Scientometrics and International Relations.

Anna Urbanovics is a PhD student at Doctoral School of Public Administration Sciences of the University of Public Service, and studies Sociology Master of Arts at the Corvinus University of Budapest. She is graduated in International Security Studies Master of Arts at the University of Public Service. She does research in Scientometrics and International Relations.

Since 1 February 2019 Minister Palkovics as Government Commissioner has been responsible for the coordination of the tasks prescribed in Act XXIV of 2016 on the promulgation of the Agreement between the Government of Hungary and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the development, implementation and financing of the Hungarian section of the Budapest-Belgrade Railway Reconstruction Project.

Since 1 February 2019 Minister Palkovics as Government Commissioner has been responsible for the coordination of the tasks prescribed in Act XXIV of 2016 on the promulgation of the Agreement between the Government of Hungary and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the development, implementation and financing of the Hungarian section of the Budapest-Belgrade Railway Reconstruction Project.

He is the past President of the Health and Health Care Economics Section of the Hungarian Economics Association.

He is the past President of the Health and Health Care Economics Section of the Hungarian Economics Association.

Based in Berlin, Zuzanna Gorenstein is Head of Project of the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK) service project “International University Rankings” since 2019. Her work at HRK encompasses the conceptual development and implementation of targeted advisory, networking, and communication measures for German universities’ ranking officers. Before joining the HRK, Zuzanna Gorenstein herself served as ranking officer of Freie Universität Berlin.

Based in Berlin, Zuzanna Gorenstein is Head of Project of the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK) service project “International University Rankings” since 2019. Her work at HRK encompasses the conceptual development and implementation of targeted advisory, networking, and communication measures for German universities’ ranking officers. Before joining the HRK, Zuzanna Gorenstein herself served as ranking officer of Freie Universität Berlin.

His books on mathematical modeling of chemical, biological, and other complex systems have been published by Princeton University Press, MIT Press, Springer Publishing house. His new book RANKING: The Unwritten Rules of the Social Game We All Play was published recently by the Oxford University Press, and is already under translation for several languages.

His books on mathematical modeling of chemical, biological, and other complex systems have been published by Princeton University Press, MIT Press, Springer Publishing house. His new book RANKING: The Unwritten Rules of the Social Game We All Play was published recently by the Oxford University Press, and is already under translation for several languages.